9 Unemployment Insurance

Sachin S. Pandya, 2021-03-09

This Chapter covers how changes in the law of unemployment insurance (UI) affected workers who became unemployed because of COVID-19. As COVID-19 hit the US and spread, and more workers became unemployed as a result, unemployed UI claimants faced the problem of getting and keeping UI benefits. Congress also pushed States to relax some UI rules, and to provide aid of its own. In Title II(A) of the CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (March 27, 2020), Congress provided for additional UI payments, including a newly-created Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (“FPUC”) benefit and a new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (“PUA”) benefit, along with eligibility rules that applied on top of, or as exceptions to, State UI eligibility rules. The result: A complex web of eligibility rules between workers and UI monetary benefits. Congress extended and modified some of these CARES Act provisions in the Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020, the name for Title II(A) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (enacted Dec. 27, 2020).

9.1 UI Eligibility

In the US, there are 53 sets of UI eligibility rules– one for each State, plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. At the same time, State UI systems are similar in many ways, in part because to get certain tax advantages, the US Department of Labor (DOL) must certify that each State’s UI system meets some basic UI conditions set by federal law. See 42 U.S.C. \(\S\) 503; 20 C.F.R. \(\S\) 604.1 - 604.6.

Typically, an applicant for UI must leap over several eligibility hurdles to receive benefits. You typically need to have earned a minimum amount from work during a year-long period prior to when you apply for UI. And you must have left your prior job involuntarily (“involuntary separation”). That means that States can deny benefits for (1) voluntarily quitting without a good enough reason (“good cause”); (2) discharge due to job-related misconduct, (3) unemployment because of a labor dispute, and (4) fraud to get or increase benefits (Department of Labor 2019, chap. 5).

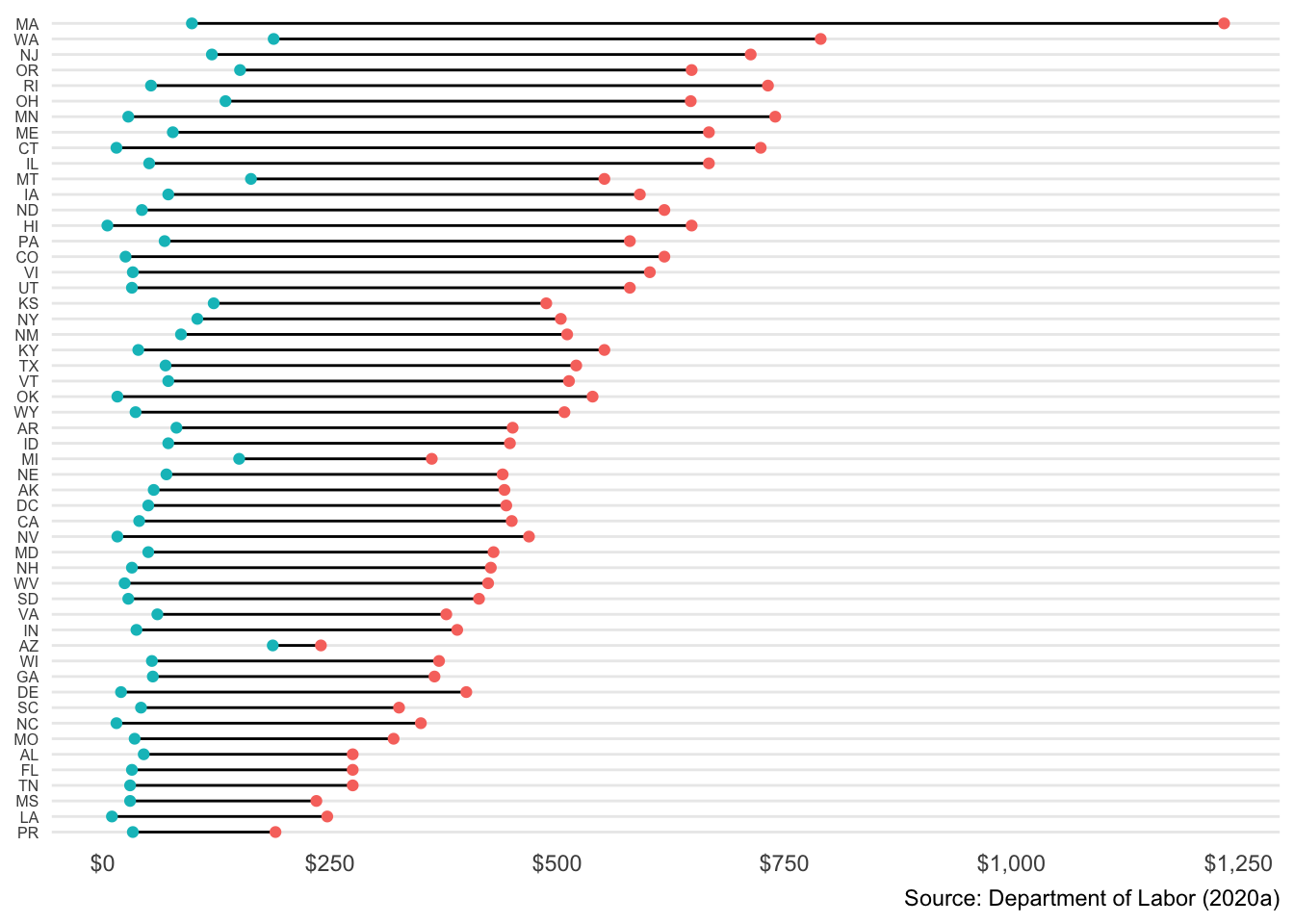

If you are eligible, the UI weekly benefit amount is typically some function of your past wages in a “base period” of time – typically the first four of the last five completed calendar quarters – as adjusted by minimum and maximum benefit amounts, which vary a lot by State (Figure 9.1; Department of Labor 2020a, cols. 2–4).

Figure 9.1: Min/Max UI Weekly Benefits by State, January 2020

Then, once you start getting UI benefits, you’ve got to do some things to keep on getting them. For the Department of Labor (DOL) to certify a State’s UI program, that State’s UI law must at least require that, “for regular compensation for any week, a claimant must be able to work, available to work, and actively seeking work.” 42 U.S.C. \(\S\) 503(a)(12).

What counts as “able”, “available”, and “actively seeking” can vary. For example, a State may take an individual as “available” to work if, say, that individual is “on temporary lay-off and is available to work only for the employer that has temporarily laid-off the individual.” 20 CFR § 604.5(a)(3). Moreover, while an individual must be “available for work,” State UI law may limit that availability to only “suitable” work so long as that doesn’t let an individual “withdraw[ ] from the labor market” while receiving UI benefits 20 C.F.R. 604.5(a)(2). Most States’ UI law limits the availability requirement to “suitable” work, though what counts as “suitable” and as a good-enough reason (“good cause”) to refuse suitable work, varies by State (Department of Labor 2019, 5–33 - 5-38).

In any case, no State UI system may deny UI benefits to an otherwise eligible individual for refusing to accept “new work . . . if the wages, hours, or other conditions of the work offered are substantially less favorable to the individual than those prevailing for similar work in the locality.” 26 U.S.C. § 3304(a)(5)(B) (emphasis added). The DOL has read “other conditions” in this statute to include “health and safety rules” and “physical conditions such as heat, light and ventilation” (Kilbane 1998). This supports reading “other conditions” to cover conditions relevant to COVID-19 exposure risk at work. But it is likely harder for UI recipients to prove that the offered new work “substantially” differs from the “prevailing” conditions for similar work, in part because some businesses have refused to report COVID-19 cases among their workers to co-employees or the public (e.g. Dungca et al. 2020; Eidelson 2020), let alone whether their workplace injury rates are above the industry average (e.g. Evans 2020).

9.2 The State UI Response

As part of the early response, State governors or agencies began relaxing or suspending some UI eligibility rules for COVID-19-related UI claims – about half the States had done this by end of March 2020 (Z. Xie 2020, appendix) – some apparently following the lead of an early DOL guidance (Pallasch 2020a). For example, Ohio’s governor declared that, under Ohio UI law, a UI applicant is unemployed and not required to “actively seek” work if the applicant is “requested by a medical professional, local health authority, or employer to be isolated or quarantined as a consequence of COVID-19 even if not actually diagnosed with COV-19,” except where the worker has “access to leave benefits from their employer(s).” Ohio E.O. 2020-03D.

When Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, Pub. L. No. 116-127, 134 Stat. 178 (2020) in mid-March 2020, Congress told DOL that, for purposes of applying its regular UI certification requirements, the DOL “shall” disregard any State modifications of UI “law and policies with respect to work search, waiting week, good cause, or employer experience rating on an emergency temporary basis as needed to respond to the spread of COVID-19.” Act § 4102(b). Thereafter, DOL issued a guidance on what temporary measures States could take. For example, DOL suggested that States modify their UI requirement that any voluntary quits must be for “good cause” to allow workers to leave work “due to reasonable risk of exposure or infection (i.e., self-quarantine) or to care for a family member affected by the virus” (Pallasch 2020a, 8).

Thereafter, some States have adopted additional COVID-19 modifications to their UI law. For example, in August 2020, the Nevada legislature directed its UI agency to “establish justifications related to COVID-19 that may constitute good cause for a person to refuse suitable work,” and provided a non-exhaustive list of such justifications. Those justifications include an unreasonable risk of workplace COVID-19 exposure of a person who, according to the Centers for Disease Control, falls within a high COVID-19 risk category; the person is caring for a child who is unable to attend school or a child care facility because of COVID-19; or the person is at or above age 65. Nevada, SB3 § 15 (Aug. 6, 2020).

9.3 FPUC: Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation

Thanks to Title II(A) of the CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 2104, 134 Stat. 281, 319 (enacted March 2020), certain workers became eligible for Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) – an additional $600 per week for weeks of unemployment ending on or before July 31, 2020, on top of what they could get in State UI benefits.

Congress initially settled on the flat $600 FPUC amount in the CARES Act, rather than making the FPUC amount depend on a claimant’s total weekly UI payment under State law. A plausible reason for a flat amount: it is harder for States to rewrite the software of their antiquated UI claims processing computer systems to implement a FPUC that varied by a claimant’s prior wages during their “base period”. Adding a flat amount is a lot easier. About a decade earlier, in 2009, 90% of State UI agencies had reported that their benefits or tax systems ran on old hardware and software programming languages, such as COBOL (average age of State UI benefits I.T. system = 22 years) (National Association of State Workforce Agencies 2010, 2). A decade later, most UI claims in 2019 were filed via the Internet, though in some States (e.g, Kansas, Vermont), many still filed by phone (Department of Labor n.d.c).

When the CARES Act passed, State UI agencies could not immediately begin processing and paying out FPUC benefits. Some States, such as New Jersey and Connecticut, put out the call for COBOL programmers to help them rewrite their code, while others argued that aging hardware or years of understaffing, not COBOL, was really to blame (Botella 2020; Hicks 2020). Rhode Island, in contrast, bypassed its legacy system and, within ten days after the CARES Act, built and deployed a separate cloud-based system for collecting, validating, and paying FPUC claims (Angell et al. 2020).

By July 2020, the flat $600 FPUC amount was still politically controversial. Some politicians complained that the $600 amount was too large, because in some cases, the total weekly UI benefit exceeded wage replacement, i.e., what what they would have received in weekly wages had they gone back to work. Research at the time and since has found little evidence that high UI amounts affected return to work (Bartik et al. 2020; Petrosky-Nadeau and Valletta 2020; Finamor and Scott 2021). As politicians debated, DOL asked state workforce agencies (which administer State UI programs), in a July 13 survey from DOL’s UI Administrator, how long it would take to implement a revised FPUC tied to a claimant’s past wages, adding “I know from our conversations with a number of you that these are heavy lifts, and we want to be able to quantify that appropriately.”(quoted in Penn 2020)

The $600 FPUC provision of the CARES Act only applied to “weeks of unemployment . . . ending on or before July 31, 2020.” CARES Act § 2104(e). Accordingly, for individuals getting UI payments for weeks of unemployment past July 31, those individuals did not get any FPUC amount. In late December 2020, Congress revived FPUC benefits for weeks of unemployment up through March 14, 2021, albeit for $300 for weeks of unemployment after December 26. Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-260, \(\S\) 203(a), H.R. 133, p. 772 (enacted Dec. 27, 2020).

9.4 PUA: Pandemic Unemployment Assistance

The CARES Act also separately provided a Pandemic Unemployment Assistance benefit (PUA) for someone who wasn’t eligible for regular or extended UI benefits under State or Federal law, including someone who had “exhausted” those benefits. CARES Act § 2102(a)(3)(A)(i). If you qualified for PUA, you would get a weekly amount equal to the State UI amount plus the flat FPUC amount that you would have been otherwise entitled to receive. CARES Act § 2102(d). Because the FPUC only covers weeks of unemployment up through July 31, 2020, the PUA amounts for weeks after July 31 are $600 less.

Originally, PUA benefits only covered “weeks of unemployment, partial unemployment, or inability to work caused by COVID–19” up through December 31, 2020. CARES Act § 2102(c)(1)(A). In late December 2020, Congress extended PUA benefit coverage to March 14, 2021. Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020, \(\S\) 201(a), H.R. 133 (enacted Dec. 27, 2020).

9.4.1 PUA Eligibility

To qualify for PUA, workers must self-certify that they were “otherwise able to work and available for work” under their State’s UI law, but they were “unemployed, partially unemployed, or unable or unavailable to work because” of one of several qualifying conditions, CARES Act § 2102(a)(3)(A)(ii)(I). While an individual is eligible for PUA even if self-employed, seeking only part-time employment, lacked sufficient work history, “or otherwise would not qualify for” regular or extended UI benefits under State or Federal law, CARES Act § 2102(a)(3)(A)(ii)(II), an individual is ineligible for PUA if they could “telework with pay” or was receiving “paid sick leave or other paid leave benefits,” CARES Act § 2102(3)(B).

PUA qualifying conditions included that the individual is caring for a family or household member diagnosed with COVID-19. CARES Act § 2102(a)(3)(A)(ii)(I)(aa)-(cc). Another PUA qualifying condition is that

a child or other person in the household for which the individual has primary caregiving responsibility is unable to attend school or another facility that is closed as a direct result of the COVID–19 public health emergency and such school or facility care is required for the individual to work;

CARES Act § 2102(a)(3)(A)(ii)(I)(dd). For this qualifying condition, DOL treats a school as “closed” even if the school system is only providing online instruction or a combination of online and in-person instruction, because the students cannot be physically present at the school on the days of online instruction. But if the school lets the individual seeking PUA choose between full-time in-person instruction and remote learning for the student, the school doesn’t count as “closed” (Pallasch 2020e).

Other PUA qualifying conditions include that the individual had to “quit his or her job as a direct result of COVID-19”; “the individual’s place of employment is closed as a direct result of the COVID-19 public health emergency”; or the individual “meets any additional criteria established by the Secretary [of Labor] for unemployment assistance under this section.” CARES Act § 2102(a)(3)(A)(ii)(I)(ii)-(kk).

In early April 2020, DOL identified “additional criteria” to address PUA eligibility for independent contractors:

[A]n individual who works as an independent contractor with reportable income may also qualify for PUA benefits if he or she is unemployed, partially employed, or unable or unavailable to work because the COVID-19 public health emergency has severely limited his or her ability to continue performing his or her customary work activities, and has thereby forced the individual to suspend such activities.

For example, even if a driver for a “ridesharing service” is treated as an independent contractor, and thus has no “place of employment” that closed due to COVID-19, the driver may still qualify for PUA “if he or she has been forced to suspend operations as a direct result of the COVID19 public health emergency, such as if an emergency state or municipal order restricting movement makes continued operations unsustainable” (Pallasch 2020c, I–6).

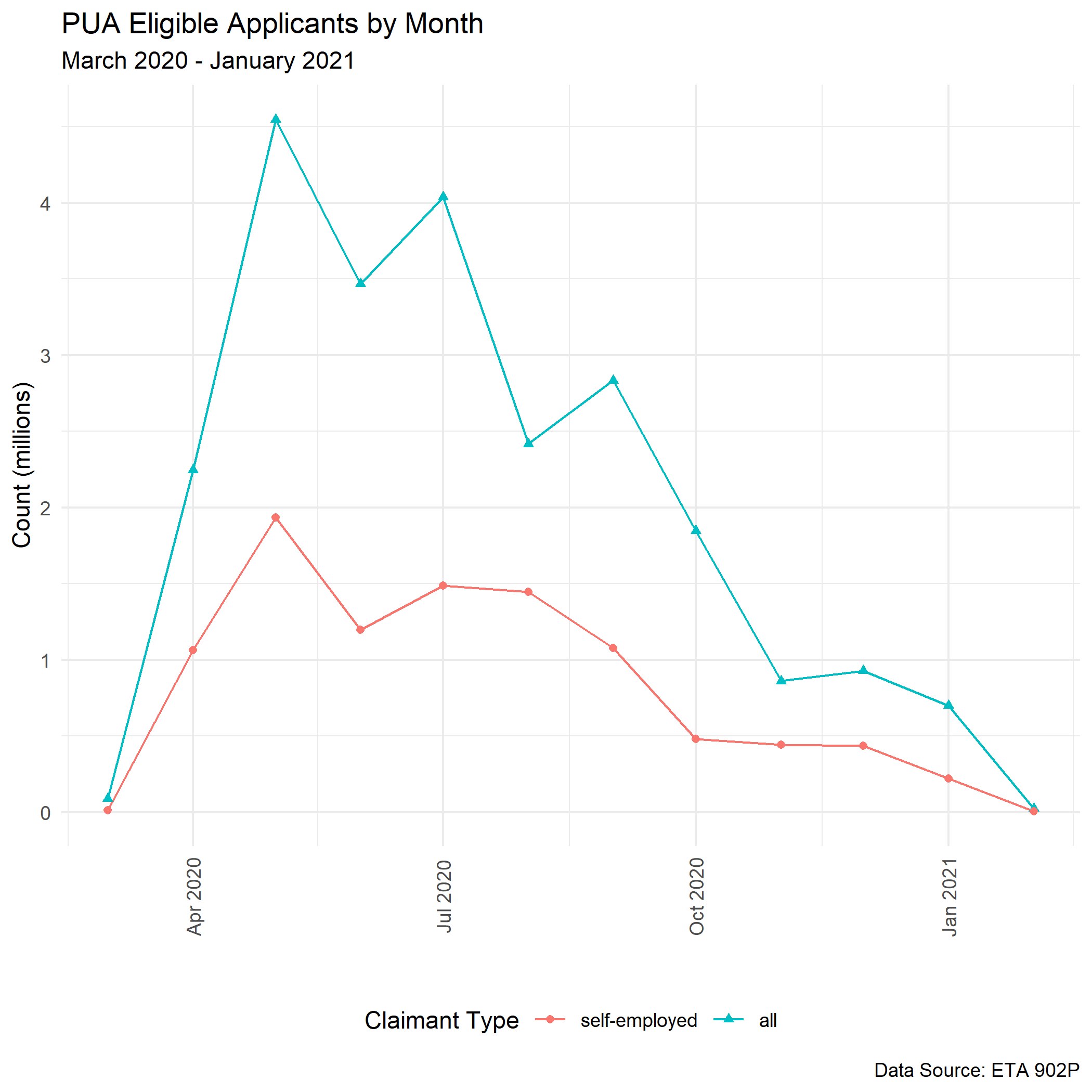

Since March 2020, millions of people have been declared eligible for PUA (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2: PUA Eligible Claimants by Month

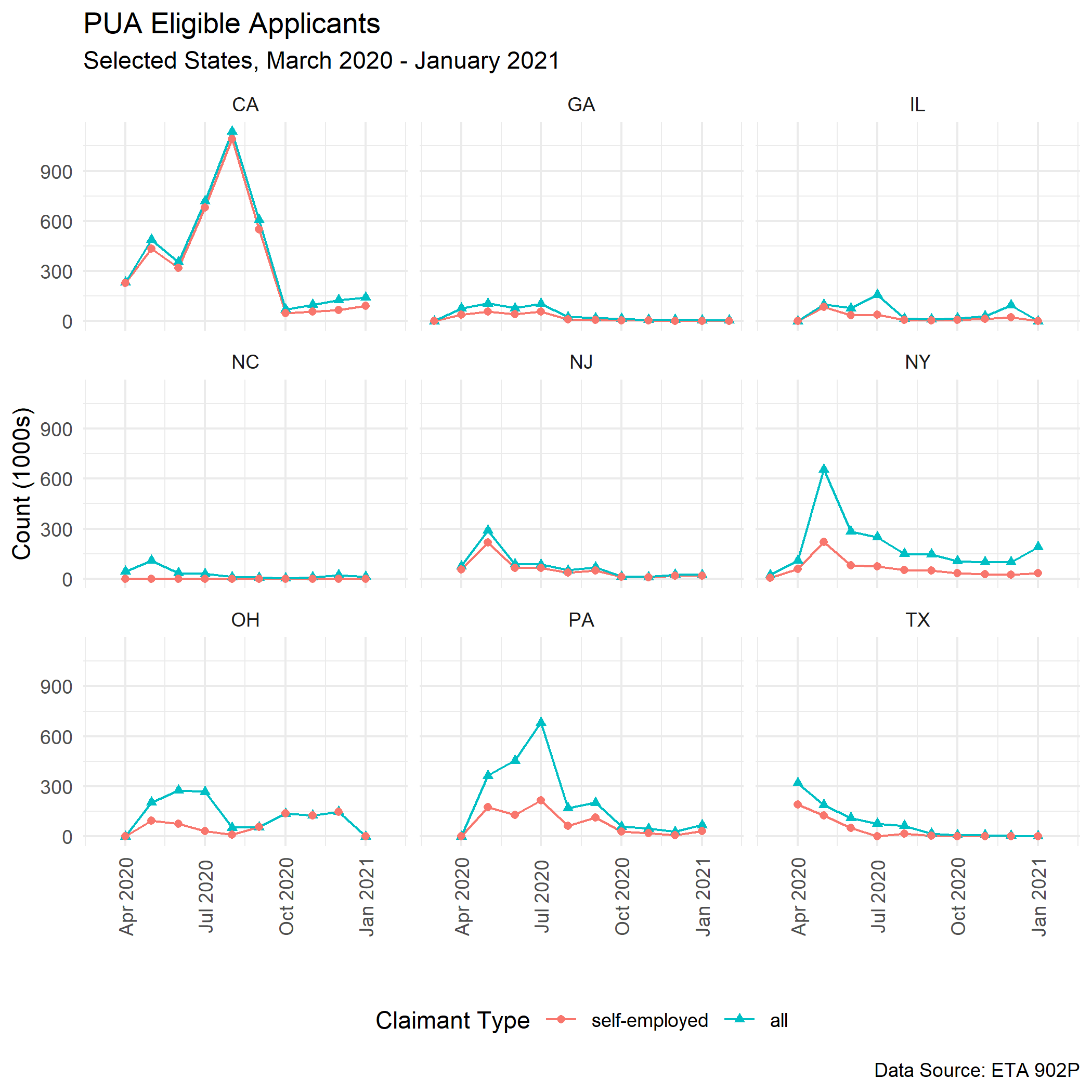

Not surprisingly, States vary as to the claimants they’ve determined eligible for PUA, and how many of those are self-employed (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3: PUA Recipients, Selected States

9.4.2 PUA Overpayment

A PUA recipient who was overpaid may be liable for the excess payment even if they didn’t know they were overpaid and even if the State UI agency made the mistake. That’s because in the CARES Act, Congress provided that the regulations that apply to federal disaster unemployment assistance, 20 C.F.R. part 625, apply to PUA benefits, unless the CARES Act section on PUA provides otherwise or “to the extent” that section conflicts with those regulations. CARES Act § 2102(h). In turn, those regulations provide that where a State UI agency finds that someone has received a disaster unemployment benefit payment that they weren’t entitled to get, that individual is “liable to repay” that payment “whether or not the payment was due to the individual’s fault or misrepresentation.” 20 C.F.R. § 625.14(a). Moreover, the State UI agency “shall take all reasonable measures” to recover the overpayment. Id. Although some State UI laws let the State UI agency waive any overpayment obligation (Department of Labor 2019, tbl. 6-1), that agency can’t waive any overpayment under these federal regulations. 20 C.F.R. § 625.14(e).

However, when Congress extended PUA coverage to March 2021, it also authorized States to waive any PUA overpayment obligation if the State finds that the individual receiving the overpayment was “without fault” and repayment “would be contrary to equity and good conscience.” Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-260, \(\S\) 201(d), H.R. 133, p. 771.

References

Angell, Mintaka, Casey Burns, Sandra Deneault, Donald Doweiko, Stephen Dziembowski, Samantha Gold, Justine S. Hastings, et al. 2020. “Delivering Unemployment Assistance in Times of Crisis.” OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/p9yk7.

Bartik, Alexander, Marianne Bertrand, Feng Lin, Jesse Rothstein, and Matthew Unrath. 2020. “Measuring the Labor Market at the Onset of the Covid-19 Crisis.” University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper, nos. 2020-83 (June). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3633053.

Botella, Elena. 2020. “Why New Jersey’s Unemployment Insurance System Uses a 60-Year-Old Programming Language.” Slate, April 9, 2020. https://slate.com/technology/2020/04/new-jersey-unemployment-cobol-coronavirus.html.

Department of Labor. 2019. Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2019/complete.pdf.

Department of Labor. 2020a. Significant Provisions of State Unemployment Insurance Laws Effective January 2020. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/content/sigpros/2020-2029/January2020.pdf.

Department of Labor. n.d.c. “UI Claims Filing Method.” Accessed August 6, 2020. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/filingmethods.asp.

Dungca, Nicole, Jenn Abelson, Abha Bhattarai, and Meryl Kornfield. 2020. “On the Front Lines of the Pandemic, Grocery Workers Are in the Dark About Risks.” Washington Post, May 24, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2020/05/24/grocery-workers-coronavirus-risks/.

Eidelson, Josh. 2020. “Covid Gag Rules at U.S. Companies Are Putting Everyone at Risk.” Bloomberg Businessweek, August 27, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-08-27/covid-pandemic-u-s-businesses-issue-gag-rules-to-stop-workers-from-talking.

Evans, Will. 2020. “How Amazon Hid Its Safety Crisis.” Reveal, September 29, 2020. https://www.revealnews.org/article/how-amazon-hid-its-safety-crisis/.

Finamor, Lucas, and Dana Scott. 2021. “Labor Market Trends and Unemployment Insurance Generosity During the Pandemic.” Economics Letters 199: 109722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109722.

Hicks, Mar. 2020. “Built to Last.” Logic, no. 11 (August). https://logicmag.io/care/built-to-last/.

Kilbane, Grace A. 1998. “Application of the Prevailing Conditions of Work Requirement.” Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 41-98. Employment and Training Administration Advisory System, Department of Labor. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL41-98.cfm.

National Association of State Workforce Agencies. 2010. “A National View of UI IT Systems.” http://itsc.org/itsc%20public%20library/NationalViewUI_IT%20Systems.pdf.

Pallasch, John. 2020a. “Unemployment Compensation (UC) for Individuals Affected by the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).” Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 10-20. Employment and Training Administration Advisory System, Department of Labor. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_10-20.pdf.

Pallasch, John. 2020c. “Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) Implementation and Operating Instructions.” Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 16-20, Attachment I. Employment and Training Administration Advisory System, Department of Labor. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_16-20_Attachment_1.pdf.

Pallasch, John. 2020e. “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 – Eligibility of Individuals who are Caregivers for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) in the Context of School Systems Reopening.” Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 16-20, Change 3. Employment and Training Administration Advisory System, Department of Labor. https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/UIPL/UIPL_16-20_Change_3.pdf.

Penn, Ben. 2020. “DOL Surveys States on ’Heavy Lifts’ of Jobless Aid Redesigns.” Bloomberg Law Daily Labor Report, July 23, 2020. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/dol-asks-states-to-detail-heavy-lifts-of-jobless-aid-redesigns.

Petrosky-Nadeau, Nicolas, and Robert G. Valletta. 2020. “Did the $600 Unemployment Supplement Discourage Work?” FRBSF Economic Letter, nos. 2020-28 (September): 1–5. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2020/september/did-600-dollar-unemployment-supplement-discourage-work/.

Xie, Zoe. 2020. “Changes in State Unemployment Insurance Rules During the Covid-19 Outbreak in the U.S.” Atlanta Fed Policy Hub, nos. 02-2020: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.29338/ph2020-02.