6 Work and Caregiving during COVID-19

Deborah A. Widiss, 2021-02-25

Even in normal times, it can be difficult to balance job duties with family responsibilities. COVID-19 has brought this conflict to a head, with schools and childcare providers operating remotely or closed, and workers called on to care for family members who become ill. Although Congress enacted limited workplace leave to address some COVID-related needs, these laws expired at the end of 2020. This Chapter explains how other laws - mostly on the books before COVID-19 - offer workers paid or unpaid leave from work for caregiving, as well as some protection from employer discrimination. These laws, while helpful, do not meet the challenge. Because women tend to pick up the slack, COVID-19 will likely worsen gender-based inequalities in ways that may persist long after the virus subsides.

6.1 Meeting Caregiving Responsibilities While Working

Many American workers regularly juggle work with caregiving for family. In 2019, before the disruption caused by the pandemic, most parents of children under 18 were employed. This is true for both married (different-sex) couples with children (in 14.7 million families out of 22.9 million, or about two-thirds, both parents were employed) and single-parent families (in 6 million out of 7.9 million families headed by mothers and 2.2 million out of 2.6 million families headed by fathers, the parent caring for children also worked) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d., tbl. 4). Single or partnered LGBT parents also are typically employed (Gates 2013). Millions of workers also provide significant support for adult family members with a disability, elderly parents, or a spouse or partner (Family Caregiver Alliance 2016).

In March 2020, because of COVID-19, schools and childcare centers across the country suddenly shut down or transitioned to remote learning. As a result, many employed parents became de facto teachers for their children while simultaneously trying to meet their own work responsibilities. Adult day care centers throughout the country also closed (Flinn 2020). As the virus spread, many workers, even if not themselves sick, cared for sick family members. At the same time, because of record levels of unemployment, individuals lucky enough to stay employed may have been reluctant to ask for any kind of special dispensation at work to help meet family-related obligations.

In summer 2020, many businesses reopened, but that only heightened the challenge. School districts across the country, including many of the nation’s largest, have operated entirely online or using a hybrid model with students attending only a few days a week, for much of the 2020-21 school year. Many childcare providers have closed; of those that are open, 86% are operating at reduced capacity and most are also incurring extra costs for personal protective and sanitation equipment (Hogan et al. 2020). Aid packages passed by the U.S. Congress in the spring 2020 fell far short of the $50 billion that childcare industry experts said is needed (Leonhardt 2020). Relief packages proposed in 2021 include significant additional funding for childcare (Luhby and Lobosco 2021). However, if Congress does not provide support, studies suggest that almost half of the nation’s childcare capacity may be lost (Jessen-Howard and Workman 2020).

Even if child and adult care centers and schools are physically open, many families fear they pose too high a risk of infection. This is especially true if anyone in the household has underlying conditions that make them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Nonetheless, workers who had been furloughed or permitted to work remotely are now being asked, or required, to come back to physical workplaces. The result is a caregiving crisis, as existing laws offer only very limited support for workers torn in too many directions.

6.2 Leave Rights for Family Caregiving

The structure and duration of time off from work, or workplace flexibility, that a worker might seek to address COVID-related family needs will vary by need and job. Some employees might ask to be off work entirely to care for an ill family member. Here, leave duration will vary with illness severity. Others might seek flexible hours over an extended period, so that they can work and also care for young children or help school-age children with remote learning. And still others might seek to work remotely so they can comply with a quarantine order.

Employees typically look first to their employer’s regular policies to address such needs. Unlike most developed countries, workers in the United States generally are not guaranteed sick leave, vacation days, personal days (Heymann et al. 2020). Nor is there a right to ask for schedule modifications to address caregiving needs.

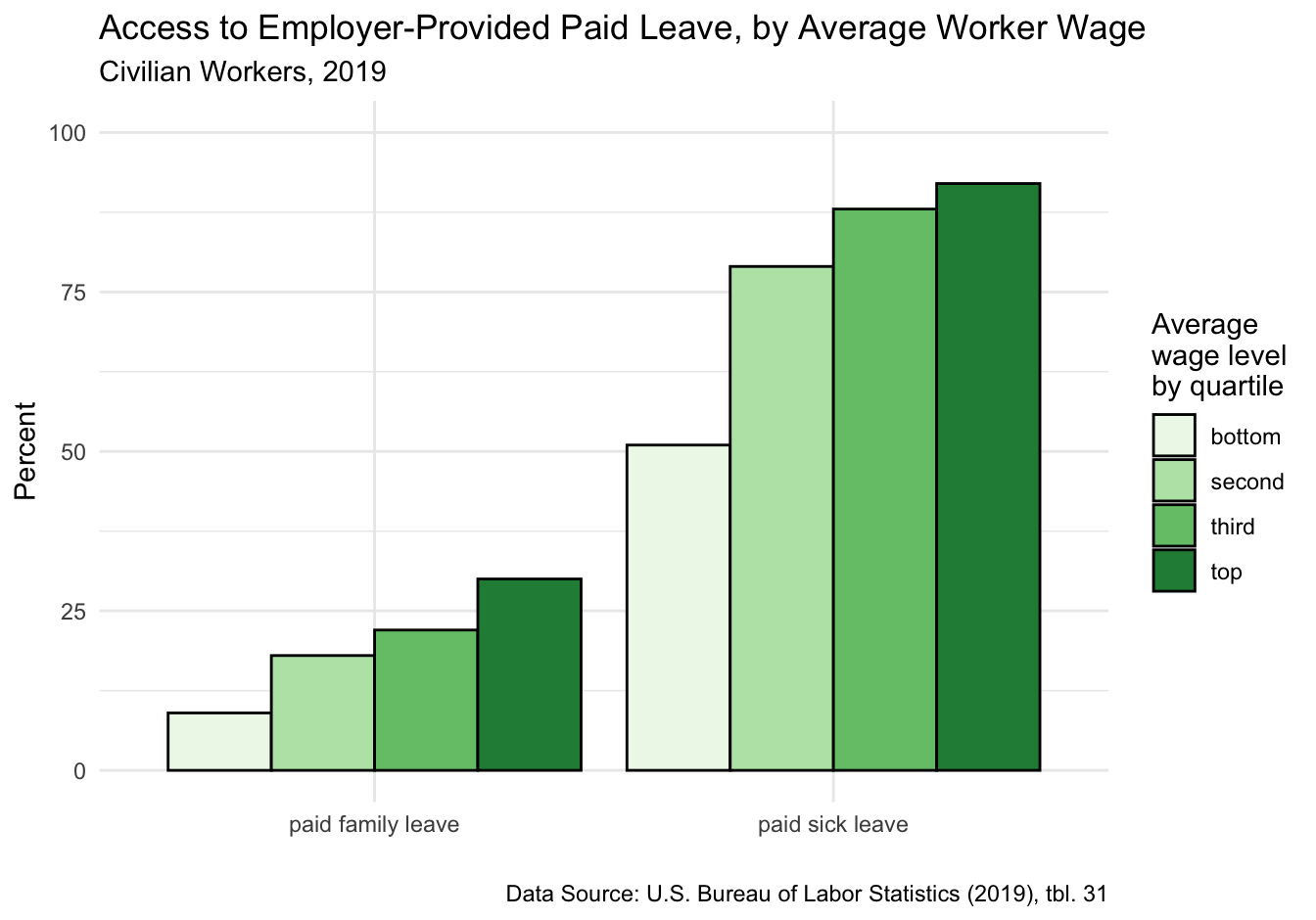

Most full-time workers receive a few weeks of paid time off per year, including paid sick days. However, lower-paid workers are less likely to receive paid sick leave than higher paid workers and fewer than half of part-time workers received paid sick days at all. Paid leave to take care of a family member who is seriously ill is relatively unusual across all wage levels (Figure 6.1; Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019b, tbl. 31).

Figure 6.1: Paid Leave by Average Worker Wage

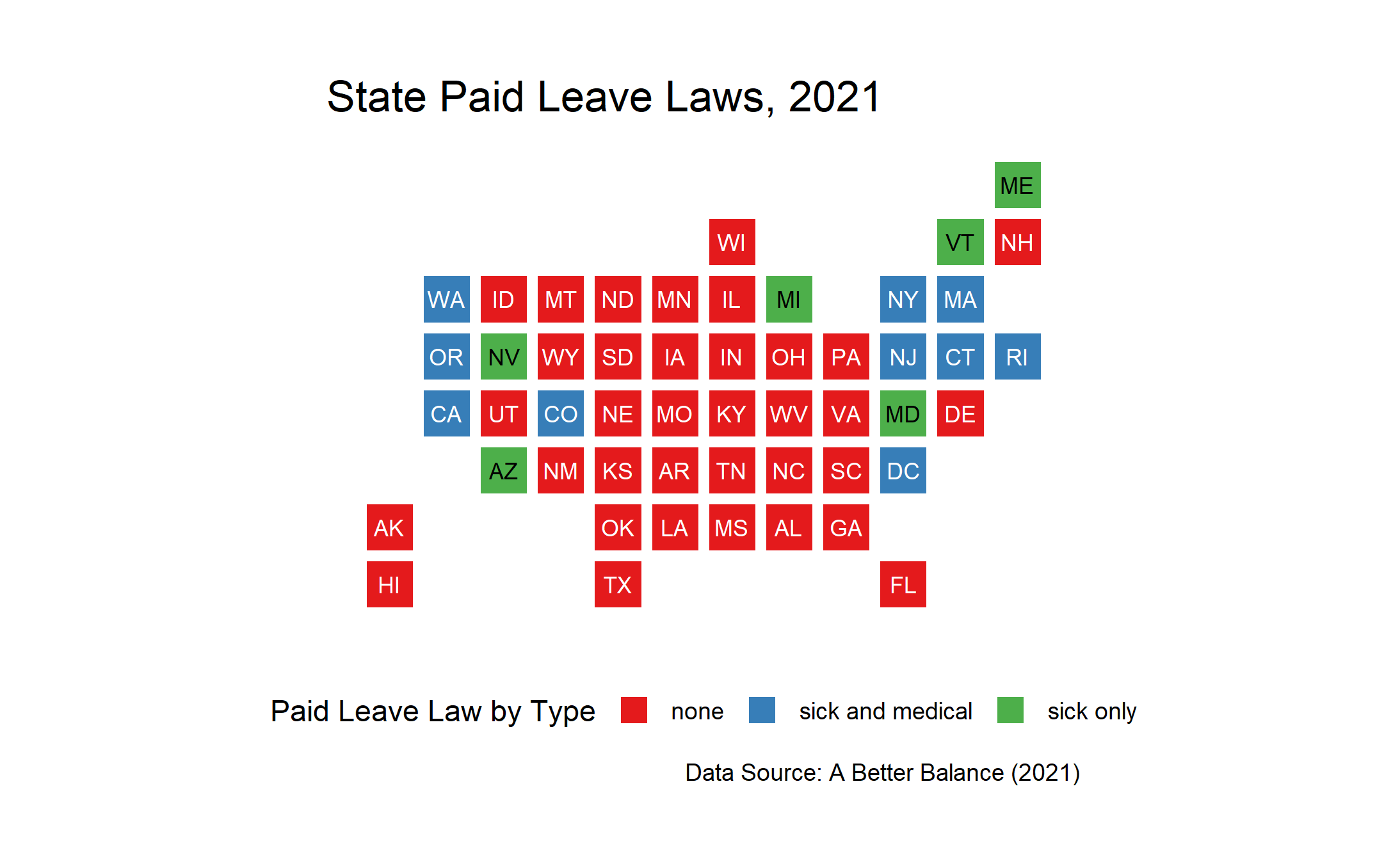

Whatever employer policies provide, some laws guarantee paid time off for certain caregiving responsibilities. These laws tend to fall into two types: (1) sick day laws, which require employers to provide a relatively limited number of days, usually at full pay, to address illness and other health-related needs; and (2) family and medical leave laws, which let a worker to take a longer period of time off, sometimes at reduced pay or no pay, to address more serious medical conditions (Figure 6.2). Both can generally be used for the health needs of the employee or close family members.

Figure 6.2: State Paid Leave Laws, 2021

While no permanent federal law guarantees paid sick days, thirteen states, the District of Columbia, and twenty-one cities and counties do (A Better Balance 2020a). Two states have laws that provide comparable amounts of paid time off for both health-related reasons and other reasons. The state and local paid sick day laws typically provide up to 40 hours per year at regular pay.

A worker may use this time to stay home if she is sick, is caring for a family member who is sick, or is seeking preventive health care. Some of these laws also apply if a business, school, or childcare provider is closed due to a public health emergency (A Better Balance 2020a). In several states, executive orders or administrative guidance issued during the pandemic has clarified that they can be used for additional COVID-specific needs, such as tests or complying with a quarantine directive. And some states and cities have passed COVID-specific paid sick day laws (A Better Balance 2021b). Additionally, in spring 2020, Congress provided a temporary right to paid sick days, which expired at the end of 2020. Emergency Paid Sick Leave Act, Pub. L. No. 116-127, §§ 5102, 5109, 134 Stat. 178, 195-198 (2020).

Paid sick day laws can help with short-term needs related to COVID-19. They do not, however, provide much relief for the longer-term disruptions that may be caused by schools operating remotely for several months, or serious cases of COVID-19.

The second group of laws, family and medical leave laws, address longer-term absences. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) requires employers to provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave to care for a spouse, son, daughter, or parent with a “serious health condition.” 29 U.S.C. § 2612(a)(1)(C); 29 C.F.R. § 825.112(a)(3). (The FMLA also requires leave to address an employee’s own serious health condition, to care for a new child, and for certain military-related care needs.) The permanent provisions of the FMLA only apply to workplaces with at least 50 employees, and employees who have worked at least 1250 hours (about 25 hours per week) for the employer in the prior year. 29 U.S.C. § 2611. These restrictions exclude about 40% of the private sector workforce (Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak 2014).

Even if an employee qualifies for FMLA leave, the permanent provisions of the FMLA address only some COVID-related caregiving needs. The FMLA regulations define “serious health condition” as a condition that causes an incapacity to work and requires either inpatient care in a hospital or continuing treatment by a health care provider. 29 C.F.R. § 825.113. A COVID-19 case that requires hospitalization or is gravely debilitating would meet this standard. A relatively mild case is less likely to qualify; the flu and colds typically do not unless they involve complications. 29 C.F.R. § 825.113(d). However, if a patient were instructed by her doctor or applicable public health orders to quarantine, and thus could not work or attend school for several days, that might satisfy the incapacity requirements. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the FMLA does not provide leave to take care of healthy children, even if they are home because of school or childcare closures (Department of Labor n.d.a). FMLA leave is also unpaid. Many workers cannot afford to be home for very long without a paycheck. (Temporary COVID-specific provisions provided some paid leave. See Chap. 6. However, these provisions expired at the end of 2020.)

Some states offer more robust support by guaranteeing paid leave for similar purposes as the FMLA provides unpaid leave. As of September 2020, eight states, and the District of Columbia, have such family and medical leave laws; approximately one quarter of Americans live in a state with a paid leave law (Widiss 2020). Typically funded by a small payroll tax, they generally offer employees between 60% and 100% of regular wages, up to a cap set at the median state wage.

These State laws cover many more workers than the FMLA, because generally there are no limits on employer size and most part-time workers are eligible (A Better Balance 2021a). In many states, independent contractors may also opt into the system. The states differ in the length of permitted leave. More recently-enacted laws generally authorize 12 weeks of benefits (although some are not yet fully phased in), while some older laws offer only 6 or 8 weeks of benefits. Like the FMLA, these laws may apply if a worker is caring for a family member with COVID-19 if it qualifies as a “serious health condition,” but they will not cover workers caring for healthy children at home because their schools or childcare providers are closed.

In sum, non-COVID-specific leave laws can offer some important to protections to workers, but they are far from sufficient to meet the full range of caregiving needs related to the pandemic.

6.3 Family Responsibilities Discrimination

While the law rarely requires employers to provide leave or otherwise accommodate their employees’ caregiving responsibilities, employers may not treat employees differently on the basis of sex, disability, race, and other prohibited factors. This means that an employer must be even-handed in how it enforces its policies, including those related to caregiving. Failure to do so may violate antidiscrimination laws (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2007). These cases are often known as “family responsibilities discrimination.”

Many of these claims concern sex discrimination. The relevant federal law, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibits employer discrimination against an individual employee because of that employee’s sex. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a). State and local laws offer analogous protections. Although employers may require that employees complete their regular workplace tasks despite caregiving responsibilities, they may not assume that women will have a harder time doing so than men, and accordingly deny women workplace opportunities. Nor may they unfairly punish men who seek to share the family caregiving load.

Under employment discrimination law, either form of differential treatment may give rise to a viable claim if the worker suffers an adverse employment action as a result. This could include being denied a job, fired, or denied a promotion. It can also include workplace harassment if the harassment is severe or pervasive enough. Additionally, the FMLA and similar state and local leave laws prohibit employers from retaliating against employees for seeking or taking authorized leave. E.g., 29 U.S.C. § 2615.

The disruptions caused by COVID-19 may increase family responsibilities discrimination by employers. If an employer considering candidates for a promotion asks a female employee, but not a male employee, whether she will be able to do the job and also care for her kids, the interviewer may have improperly relied on a sex-based stereotype. Likewise, if an employer modifies its usual policies to allow a woman to work at home because her children’s school is closed, but refuses to allow a male employee to do the same, the man may have suffered unlawful discrimination. Or if a supervisor regularly harasses an employee in sexist terms because the employee’s children are visible during Zoom-based meetings, the supervisor may have acted illegally.

Anecdotal reports suggest such discrimination may be widespread in the COVID-era. Between April and June 2020, caregiver-related calls to The Center for WorkLife Law’s hotline for employees increased by 250% compared to the same time in 2019 (Williams 2020). And, in a July 2020 online survey of salaried employees in the U.S. (n = 1,051), 34% of men with children at home, as compared to 9% of women with children at home, said they received a promotion while working remotely (Rogers 2020).

6.4 Effects on Gender Equality

Women typically bear a disproportionate share of the caregiving burden, even if they are also working full time for pay outside the home (e.g., Patten 2015). Emerging studies suggest that the pandemic has, in many families, exacerbated such inequalities. Women are far more likely than men to disrupt their work days to meet their children’s needs or other caregiving responsibilities (e.g., Zamarro and Prados 2020; Collins et al. 2021).

The caregiving challenges caused by COVID are likely to persist or worsen, particularly since many schools are operating remotely in fall 2020. Workers are, quite simply, being stretched too thin – and women are far more likely to leave the workforce than men. This is already happening. In September 2020, 865,000 women, as compared to 216,000 men, dropped out of the labor force (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020a, tbl. A-1). This will cause significant financial hardship to many families, and it will widen gender gaps in earnings and retirement security. Parents who can’t afford to quit working, particularly single parents, may have to rely on inadequate and unstable childcare arrangements, or simply leave kids home alone.

There is, however, a glimmer of hope. Although women are doing a greater share of caregiving, men are also shouldering enhanced responsibilities (e.g. Krentz et al. 2020). Fathers may remain more involved even when the crisis subsides. The pandemic has also spotlighted how essential childcare, schools, and adult care facilities are for a productive workforce. This has bolstered public support for policies such as paid family leave and universal childcare. Already, a few states have responded to the COVID crisis by enacting permanent leave provisions. E.g., SB 20-205 (Colorado). If this trend continues, the pandemic could spur more general legislative reform that could help families better balance work and caregiving needs, both now and in the future.

References

A Better Balance. 2020a. “Overview of Paid Sick Time Laws in the United States.” https://www.abetterbalance.org/paid-sick-time-laws/?export.

A Better Balance. 2021a. “Comparative Chart of Paid Family and Medical Leave Laws in the United States.” February 10, 2021. https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/paid-family-leave-laws-chart/.

A Better Balance. 2021b. “Emergency Paid Sick Leave Tracker: State, City, and County Developments.” https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/emergencysickleavetracker/.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020a. “The Employment Situation - September 2020.” USDL-20-1838. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019b. “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2019.” Bulletin 2791. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2019/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2019.pdf.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. n.d. “Employment Characteristics of Families - 2019.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf.

Collins, Caitlyn, Liana Christin Landivar, Leah Ruppanner, and William J. Scarborough. 2021. “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours.” Gender, Work & Organization 28 (S1): 101–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506.

Department of Labor. n.d.a. “COVID-19 and the Family and Medical Leave Act Questions and Answers.” Accessed September 3, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla/pandemic.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. 2007. “Enforcement Guidance: Unlawful Disparate Treatment of Workers with Caregiving Responsibilities.” No. 915.002. https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/enforcement-guidance-unlawful-disparate-treatment-workers-caregiving-responsibilities.

Family Caregiver Alliance. 2016. “Caregiver Statistics: Work and Caregiving.” https://www.caregiver.org/print/23248.

Flinn, Brendan. 2020. “States Take Action to Sustain Adult Day Services Through Covid-19.” Leading Age. April 9, 2020. https://leadingage.org/regulation/states-take-action-sustain-adult-day-services-through-covid-19.

Gates, Gary J. 2013. “LGBT Parenting in the United States.” The Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Parenting-US-Feb-2013.pdf.

Heymann, Jody, Amy Raub, Willetta Waisath, Michael McCormack, Ross Weistroffer, Gonzalo Moreno, Elizabeth Wong, and Alison Earle. 2020. “Protecting Health During Covid-19 and Beyond: A Global Examination of Paid Sick Leave Design in 193 Countries.” Global Public Health 15 (7): 925–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1764076.

Hogan, Lauren, Michael Kim, Aaron Merchen, Johnette Peyton, Lucy Recio, and Henrique Siblesz. 2020. “Holding on Until Help Comes: A Survey Reveals Child Care’s Fight to Survive.” National Association for the Education of Young Children. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf.

Jessen-Howard, Steven, and Simon Workman. 2020. “Coronavirus Pandemic Could Lead to Permanent Loss of Nearly 4.5 Million Child Care Slots.” Center for American Progress. April 24, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/news/2020/04/24/483817/coronavirus-pandemic-lead-permanent-loss-nearly-4-5-million-child-care-slots/.

Klerman, Jacob Alex, Kelly Daley, and Alyssa Pozniak. 2014. “Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report.” Abt Associates, Inc. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/legacy/files/FMLA-2012-Technical-Report.pdf.

Krentz, Matt, Emily Kos, Anna Green, and and Jennifer Garcia-Alonso. 2020. “Easing the Covid-19 Burden on Working Parents.” BCG. May 21, 2020. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/helping-working-parents-ease-the-burden-of-covid-19.

Leonhardt, Megan. 2020. “Republicans’ Relief Plan Includes $15 Billion Bailout of the Childcare Industry—but It Falls Short of What’s Needed, Advocates Say.” CNBC, July 28, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/28/republicans-15-billion-bailout-of-child-care-industry-falls-short.html.

Luhby, Tami, and Katie Lobosco. 2021. CNN Wire. February 20, 2021. https://abc7ny.com/stimulus-update-third-check-democrats-covid-relief-bill-biden-plan/10356610/.

Patten, Eileen. 2015. “How American Parents Balance Work and Family Life When Both Work.” Pew Research Center. November 4, 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/11/04/how-american-parents-balance-work-and-family-life-when-both-work/.

Rogers, Ben. 2020. “Not in the Same Boat: Career Progression in the Pandemic.” Qualtrics Blog. August 26, 2020. https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/inequitable-effects-of-pandemic-on-careers/.

Widiss, Deborah A. 2020. “Equalizing Parental Leave.” Indiana Legal Studies Research Paper No. 3587979. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3587979.

Williams, Joan C. 2020. “Real Life Horror Stories from the World of Pandemic Motherhood.” New York Times, August 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/06/opinion/mothers-discrimination-coronavirus.html.

Zamarro, Gema, and María J. Prados. 2020. “Gender Differences in Couples’ Division of Childcare, Work and Mental Health During Covid-19.” https://cesr.usc.edu/documents/WP_2020_003.pdf.