8 Pregnant Employees and New Parents

Deborah A. Widiss, 2020-12-01

Pregnant women and new parents may have specific challenges connected to work during the COVID pandemic. This chapter summarizes federal and state laws that pregnant women may use to reduce risk of exposure to COVID; that provide new parents time off after a birth; and that protect against discrimination for employees who ask for support. Existing laws, however, provide expecting and new parents inadequate support.

8.1 Reducing COVID-19 Exposure When Pregnant

Early studies suggest pregnant women who contract COVID-19 are more likely to suffer serious complications requiring admission to an intensive care unit, and they are more likely to have a pre-term birth (Allotey et al. 2020; Zambrano et al. 2020; Woodworth et al. 2020). Moreover, we do not yet know how a mother’s illness might affect a fetus, particularly if the mother were sick during early months of pregnancy (Wadman 2020).

To reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19, many pregnant women may ask for accommodations at work. Common requests include seeking to work remotely, even if other employees are returning to physical workplaces; transfer to a position with a low amount of contact with customers or co-workers; or high-quality personal protective equipment or physical barriers that can reduce the risk of exposure. Employees might also seek a job-protected paid or unpaid leave. Some employers voluntarily grant such requests. If an employer refuses to do so, federal and state legal protections can be helpful in some cases, but are insufficient to fully meet these needs.

First, temporary federal laws, passed in response to the crisis, provide short-term paid sick leave and family leave. (See Chapter 7). These laws are relevant if the worker, or someone in her family, has already contracted COVID-19, or if schools or daycares have been closed because of COVID. However, they generally will not apply to workers who simply seek to avoid exposure to the virus.

The second set of laws that may be relevant are disability laws. The Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of a disability and requires employers to provide “reasonable accommodations” to individuals with a disability, unless doing so would be an undue hardship. 42 U.S.C. 12112(b). State and local disability laws often offer similar protections, and sometimes cover smaller employers than the ADA does. E.g., Colo. Rev. Stat. 24-34-402; Conn. Gen. Stat. 46a-60. Under the ADA, a disability is defined in part as an “impairment” that “substantially limits” an individual’s ability to conduct “one or more major life activities”. 42 U.S.C. 12102(1). A COVID-19 infection may qualify as a disability, depending on the level of impairment it causes (See 13.1).

Although healthy pregnancies are generally not considered a disability, 29 C.F.R. 1630.2(h), pregnancy-related complications may be (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2020b, J.2). A pregnant worker may also have other pre-existing disabilities that interact with the pregnancy and the pandemic in ways that might call for special supports. For example, if an employee has gestational diabetes or respiratory conditions connected to the pregnancy, those could likely qualify as a disability. And since such conditions might put the employee at greater risk if she were to contract COVID, she might be able to ask for measures that reduce such risk as a reasonable accommodation (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2020b, G3). Likewise, if the employee had a preexisting mental health condition, such as an anxiety disorder, that qualifies as a disability, the employee might be able to request to work at home or take other steps to mitigate the risk of infection as way of accommodating anxiety that is exacerbated by being pregnant during pandemic (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2020b, D.2).

Third, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) prohibits discrimination against pregnant employees and requires that employers provide the “same” level of support to pregnant employees that they provide to other employees with comparable ability or inability to work. 42 U.S.C. 2000e(k). If an employer has allowed other workers to take steps to reduce exposure to the virus, it may be required to provide comparable support to pregnant employees or at least a sufficient legitimate non-discriminatory rationale for the different treatment. Young v. United Parcel Service, 135 S. Ct. 1338 (2015).

Finally, thirty states have passed laws that explicitly require employers to provide reasonable accommodations for pregnancy, childbirth, and related medical conditions (???). These laws sidestep the question of whether the medical condition at issue can qualify as a “disability”, as well as the comparative assessment required by the PDA. Under these laws, pregnant employees might be able to request accommodations that would reduce the risk of COVID infection, such as the option to work at home, or otherwise respond to the particular needs of pregnant women during the pandemic.

8.2 Time Off During Pregnancy or to Care for a New Baby

Most birth mothers need to take some time off work to recover from childbirth, and new parents – both male and female – often want to take some time to bond with a new baby. Additionally, a pregnant women might seek a job-protected leave during her pregnancy. The United States is the only developed country that fails to guarantee paid time off for new parents (Widiss 2020). Instead, parents rely on a patchwork of protections, and their employers’ own discretionary policies.

Under federal law, the primary source of leave rights for new parents is the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). 29 U.S.C. 2612(a)(1)(A). The FMLA only applies to workplaces with at least 50 employees, and to employees who have worked for the employer for at least a year on a full-time or close to full-time basis. 29 U.S.C. 2611. These restrictions exclude about 40% of employees, as well as independent contractors and self-employed workers (Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak 2014).

If eligible, a new parent, including adoptive or foster parents, can take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave under the FMLA. The FMLA also provides leave for an individual’s own serious medical condition, or to care for a family member with a serious medical condition. The 12-week cap, however, is cumulative within a calendar year, or alternative 12-month period chosen by the employer (Department of Labor 2013). This means that if a pregnant employee has taken time off under the FMLA for a medical condition, including the emergency paid leave provided under the FMLA for coronavirus-related needs, she may have exhausted her leave rights before the baby is even born (Department of Labor n.d.b, Question 45).

A growing number of state laws supplement the FMLA by providing paid leave for new parents, also as part of more general family and medical leave laws (A Better Balance 2020b). Most apply regardless of employer size, and they provide partial wage replacement, generally up to a cap set around the state’s average wage. Most also cover part-time employees, and many permit independent contractors to opt into the program. The laws are typically funded by a small payroll tax.

These laws generally provide each new parent between eight and twelve weeks of leave, usually known as “bonding leave”, to care for a new child. They are available to biological parents, and also generally to parents after an adoption or foster placement.

Additionally, in some states, a birth mother can receive benefits for the full allotment of “bonding” leave and separately receive benefits for a period of “medical” leave. This could include time during the pregnancy, delivery, or recovery period in which she is unable to work, or other medical needs that occur during the relevant year. In other words, this is different from the FMLA’s structure, in that all leave rights under the FMLA are collectively subject to the 12-week annual cap.

Some of these laws provide income but do not technically reserve an employee’s job. However, the employee may be able to combine the benefits under these laws with FMLA-protections or an employer’s own leave policy. These laws are a very important step forward as compared to the prior baseline; however, since the leave rights are individual to each parent, single-parent families are eligible to receive only half as much leave (Widiss 2020).

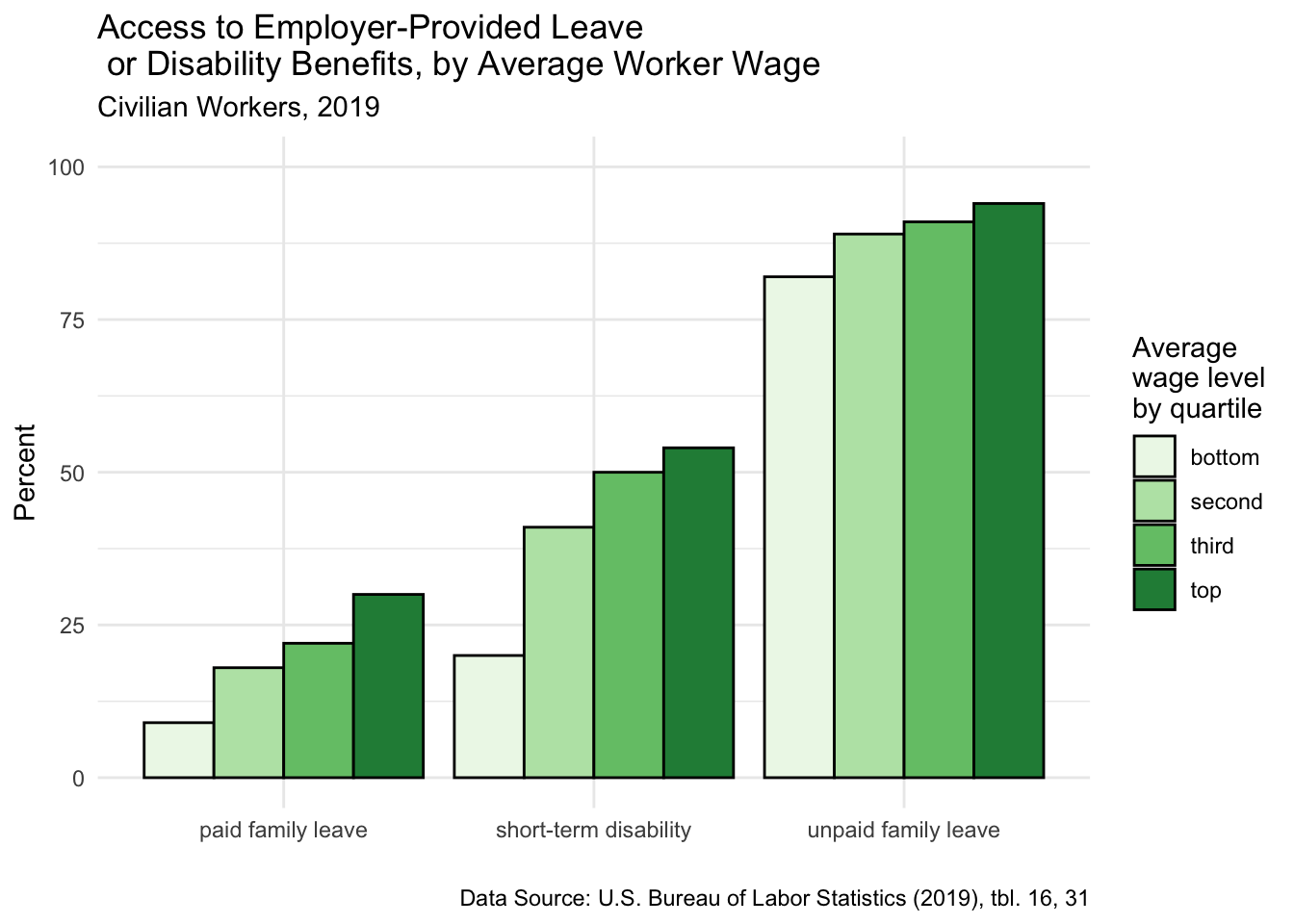

Employers also sometimes choose to provide paid or unpaid leave to new parents as a matter of voluntary benefits. Although paid leave is quite rare, especially for lower-wage workers, unpaid leave is relatively standard. Moreover, some employers provide short-term disability benefits, which provide full or partial income replacements during a period of medical incapacity (Figure 1, Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019b, tbl. 16, 31). Birth mothers can usually access short-term disability benefits during the period of time that they are physically recovering from childbirth, typically a period of 6 to 8 weeks.

8.3 Discrimination Against Pregnant Employees or New Parents

Pregnant employees or new parents may also face discrimination at work. A September 2020 review of COVID-19 workplace case filings identified lawsuits by pregnant employees as particularly prevalent. In all of the cases reviewed, the pregnant employee had allegedly asked for accommodations or a furlough to reduce her risk of COVID-19 exposure, after which the employer fired her (Camire, Meneghello, and Nesbit 2020).

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act makes clear that adverse actions against an employee because of pregnancy, breastfeeding, or related medical conditions are illegal. 42 U.S.C. 2000e(k). It is also illegal to retaliate against employees for asking for accommodations under federal or state disability laws, under state pregnancy accommodation laws, or for seeking or using FMLA leave or state paid leave laws. However, in many such cases, the employer will argue that it fired the employee for other legitimate reasons, such as performance problems. In those cases, a plaintiff’s odds of success depends on marshaling enough evidence to undermine this justification. This could done, for example, by identifying other employees with similar performance records who were not terminated, or comments by decision-makers suggesting discriminatory bias or stereotypical assumptions, such as that pregnant employees are less competent or committed than other employees.

8.4 Unemployment Insurance

Pregnant employees may feel they have to quit work, particularly employees who have requested and been refused accommodations to mitigate risk of exposure. New parents likewise may feel they need to quit to provide care, especially because many childcare centers are closed or operating at a reduced capacity. In many states, during normal times, employees who quit a job for family-related care needs are not eligible for unemployment insurance (Ben-Ishai, McHugh, and Ujvari 2015). However, Congress and some States have provided temporary unemployment insurance eligibility for some workers in this situation. E.g. CARES Act 2102(a)(3)(A)(ii)(I)(dd), 134 Stat. 313; Nevada, SB3 15(5) (Aug. 6, 2020).

References

A Better Balance. 2020b. “State Pregnant Workers Fairness Laws.” November 6, 2020. https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/pregnant-worker-fairness-legislative-successes/.

Allotey, John, Elena Stallings, Mercedes Bonet, Magnus Yap, Shaunak Chatterjee, Tania Kew, Luke Debenham, et al. 2020. “Clinical Manifestations, Risk Factors, and Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Pregnancy: Living Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ 370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3320.

Ben-Ishai, Liz, Rick McHugh, and Kathleen Ujvari. 2015. “Access to Unemployment Insurance Benefits for Family Caregivers: An Analysis of State Rules and Practices.” AARP Public Policy Institute. https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Access-to-Unemployment-Insurance-Benefits-for-Family-Caregivers.pdf.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019b. “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2019.” Bulletin 2791. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2019/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2019.pdf.

Camire, Melissa, Richard Meneghello, and Kristen Nesbit. 2020. “Breaking down the Top 3 Covid-19 Workplace Claims.” Law360, September. https://www.law360.com/florida/articles/1312309/breaking-down-the-top-3-covid-19-workplace-claims.

Department of Labor. 2013. “Fact Sheet #28H: 12-Month Period Under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).” February 2013. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/whdfs28h.pdf.

Department of Labor. n.d.b. “Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Questions and Answers.” Accessed November 19, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pandemic/ffcra-questions.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. 2020b. “What You Should Know About COVID-19 and the ADA, the Rehabilitation Act, and Other EEO Laws.” December 16, 2020. https://www.eeoc.gov/wysk/what-you-should-know-about-covid-19-and-ada-rehabilitation-act-and-other-eeo-laws.

Klerman, Jacob Alex, Kelly Daley, and Alyssa Pozniak. 2014. “Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report.” Abt Associates, Inc. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/legacy/files/FMLA-2012-Technical-Report.pdf.

Wadman, Meredith. 2020. “COVID-19 Unlikely to Cause Birth Defects, but Doctors Await Wave of Fall Births.” Science Magazine. August 4, 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/08/why-pregnant-women-face-special-risks-covid-19.

Widiss, Deborah A. 2020. “Equalizing Parental Leave.” Indiana Legal Studies Research Paper No. 3587979. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3587979.

Woodworth, Kate R., Emily O’Malley Olsen, Varsha Neelam, Elizabeth L. Lewis, Romeo R. Galang, Titilope Oduyebo, Kathryn Aveni, et al. 2020. “Birth and infant outcomes following laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy—SET-NET, 16 jurisdictions, March 29–October 14, 2020.” MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69 (44): 1635–40. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e2.

Zambrano, Laura D., Sascha Ellington, Penelope Strid, Romeo R. Galang, Titilope Oduyebo, Van T. Tong, Kate R. Woodworth, et al. 2020. “Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed Sars-Cov-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status—United States, January 22–October 3, 2020.” MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report 69 (44): 1641–7. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3.